Overview of Anxiety Disorders

What Is Anxiety? Anxiety is a normal human response to stress or perceived danger. Feeling anxious before a big exam or during a difficult life event is expected and even useful – it can sharpen focus and alert us to risks.1 In healthy amounts, anxiety triggers the “fight-or-flight” response, which raises heart rate and stress hormones to help us tackle challenges.2 However, anxiety becomes problematic when it is excessive, persistent, or out of proportion to the situation.1 In anxiety disorders, these feelings of fear, dread, or nervousness occur frequently or intensely enough to interfere with daily life.1 People with an anxiety disorder often cannot easily control their anxious responses and experience pronounced physical symptoms like a racing heart, sweating, or trembling even in safe or routine situations. 1

Types of Anxiety Disorders: There are several diagnosable anxiety disorders, each with distinct features:1

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD): Characterized by excessive, ongoing worry about a variety of everyday issues (work, health, finances, etc.) that is difficult to control. People with GAD often feel on edge or overwhelmed almost every day, along with physical symptoms like muscle tension, fatigue, or difficulty sleeping.1

- Panic Disorder: Marked by recurrent panic attacks – sudden episodes of intense fear that peak within minutes, accompanied by symptoms like heart palpitations, chest pain, shortness of breath, dizziness, or feeling of loss of control. These attacks often occur unpredictably, and the person then worries about having future attacks.1 (Some individuals with panic disorder also develop agoraphobia, avoiding places where escape or help might be difficult during a panic episode.)1

- Social Anxiety Disorder (Social Phobia): Involves an intense, persistent fear of social or performance situations where one might be judged, criticized, or embarrassed. Everyday interactions – meeting new people, speaking up in a group, or eating in public – can provoke crippling anxiety, blushing, or nausea. Sufferers often avoid social situations or endure them with severe distress.1

- Specific Phobias: These are strong, irrational fears of specific objects or situations (like heights, spiders, flying). The fear is disproportionate to the actual danger, but encountering the phobic trigger evokes immediate anxiety or panic. People go to great lengths to avoid the phobic stimulus, even though they recognize the fear is excessive.1 (Hundreds of phobias exist; aside from agoraphobia, they are classified under the umbrella of “specific phobia.”)

- Other Forms: Additional anxiety-related diagnoses include Separation Anxiety Disorder (extreme anxiety when apart from loved ones), Selective Mutism (inability to speak in certain situations due to anxiety), as well as related conditions like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) which have overlapping features but are categorized separately.1

Despite their differences, all anxiety disorders produce a mix of psychological symptoms (excessive fear, worry, irritability, trouble concentrating) and physical symptoms (restlessness, rapid heartbeat, chest tightness, hyperventilation, sweating, GI upset, etc.)1 These symptoms reflect an overactivation of the body’s stress response in situations where it shouldn’t be triggered so strongly.

What Causes Anxiety Disorders?

Anxiety disorders do not have a single simple cause – they arise from a combination of factors.1 Medical experts and researchers point to influences that include:

- Brain Chemistry Imbalances: Abnormal levels of neurotransmitters (brain chemicals) such as serotonin, dopamine, and GABA are linked to anxiety.1 These chemicals regulate mood and fear responses; an imbalance (for example, low serotonin or GABA, which normally have calming effects) can make someone more prone to anxiety and hypervigilance.

- Brain Circuit Overactivity: The amygdala, a brain region that processes fear, tends to be hyperactive in anxiety disorders.1 This means the brain may misinterpret harmless situations as threatening, continuously firing off fear signals. In short, the brain’s “alarm system” is oversensitive or stuck in the “on” position.

- Genetics: Anxiety disorders often run in families. Having a first-degree relative (parent or sibling) with an anxiety disorder increases one’s risk of developing anxiety.1 This suggests a hereditary component – specific genes affecting brain chemistry or stress reactivity may be passed down.

- Chronic Stress or Trauma: Environmental and lifestyle factors are pivotal. Exposure to prolonged stress – such as financial hardship, abuse, unstable environments – can dysregulate the nervous system’s stress response and contribute to anxiety.1 A traumatic experience (e.g. violence, accident) is a known trigger for disorders like PTSD and can also precipitate generalized anxiety or panic disorder. Essentially, life experiences can “wire” the brain and nervous system toward an anxious mode, especially if trauma occurs in childhood or stress is severe and ongoing.1

It’s important to note that experiencing anxiety is never a character flaw or a matter of willpower. These are real medical conditions rooted in brain and body processes.1 Often it’s a combination of the above factors – for example, an inherently sensitive temperament or genetic predisposition, combined with stressful life events and neurochemical changes – that ultimately leads to an anxiety disorder.1 Because multiple systems are involved (from brain circuitry to hormones to life stressors), treatment typically needs to be comprehensive as well.

Conventional Treatments for Anxiety Disorders

Treating anxiety usually involves a two-pronged approach: psychotherapy (counseling) to address the thoughts and behaviors driving anxiety, and medication to relieve symptoms. According to the Cleveland Clinic and other leading authorities, a combination of therapy and medication is often most effective.1 Each individual is different, and clinicians tailor treatment plans to the person’s specific symptoms and circumstances.1 Common evidence-based treatments include:

- Psychotherapy: Talk therapy can significantly reduce anxiety by helping people understand and manage their thought patterns. The most common form is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), which teaches strategies to reframe anxious thoughts and gradually face feared situations so that anxiety diminishes over time.1 For example, someone with social anxiety might do CBT exercises to challenge the belief “everyone is judging me” and slowly engage in social interactions with coaching, until their confidence grows. Exposure therapy is another technique particularly useful for phobias and PTSD – it involves controlled, repeated exposure to the feared object or memory in a safe environment to desensitize the person’s response.1 Over weeks of therapy, many patients learn how to calm themselves and regain control in situations that used to trigger panic.

- Medications: While not a cure for anxiety, medications can relieve symptoms and restore normal functioning.1 Several classes of drugs are used:

- Antidepressants: Specifically, SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) and SNRIs are first-line medications for chronic anxiety.1 Examples include sertraline, escitalopram, (SSRIs) or SNRIs. These medications gradually readjust neurotransmitter levels (like raising serotonin) to improve mood stability and stress resilience. They typically take a few weeks to take full effect. Research shows SSRIs/SNRIs can significantly reduce excessive worry, phobic anxiety, and panic frequency in many patients.1

- Benzodiazepines: This drugs are tranquilizers that quickly quell acute anxiety by enhancing GABA (an inhibitory neurotransmitter)1. They can stop a panic attack or severe anxiety spike within 30-60 minutes, inducing calm. However, benzodiazepines carry risks: one can develop tolerance (needing higher doses for same effect) and dependence, and they can cause drowsiness or confusion.1 For this reason, they are usually prescribed short-term or for as-needed use (e.g. during a crisis or while waiting for an SSRI to kick in)1.

- Beta-Blockers: These are heart/blood pressure medications that are sometimes used off-label to control the physical symptoms of anxiety, such as rapid heartbeat, shaking, or sweating1. Beta-blockers don’t affect psychological worry, but by blunting the adrenaline effects on the body, they can be helpful for performance anxiety1.

- Other medications can include certain anticonvulsants or antipsychotics in low doses for augmentation, an anti-anxiety drug specifically for GAD. The best choice varies per individual. Importantly, medication should be monitored by a healthcare provider; it often takes some trial-and-error to find the optimal drug and dose that eases anxiety without significant side effects.1

- Lifestyle and Support: In addition to formal therapy and meds, doctors usually encourage self-care strategies. Regular exercise, adequate sleep, and reducing caffeine/alcohol can all help regulate mood and anxiety levels. Stress management techniques (like deep breathing exercises, yoga, meditation) are complementary tools that many find beneficial alongside their primary treatment.2 Support groups or anxiety education programs can also provide encouragement and practical tips from others who have managed similar issues.

Overall, conventional treatments are often effective – the majority of people with anxiety disorders see improvement with therapy, medication, or both.1 However, not everyone achieves full remission, and some may experience residual symptoms or side effects from medications. This has driven interest in root-cause approaches that go beyond symptom suppression – in particular, approaches targeting the body’s stress-response system (the nervous system) which underlies the experience of anxiety.

Anxiety and Nervous System Dysregulation

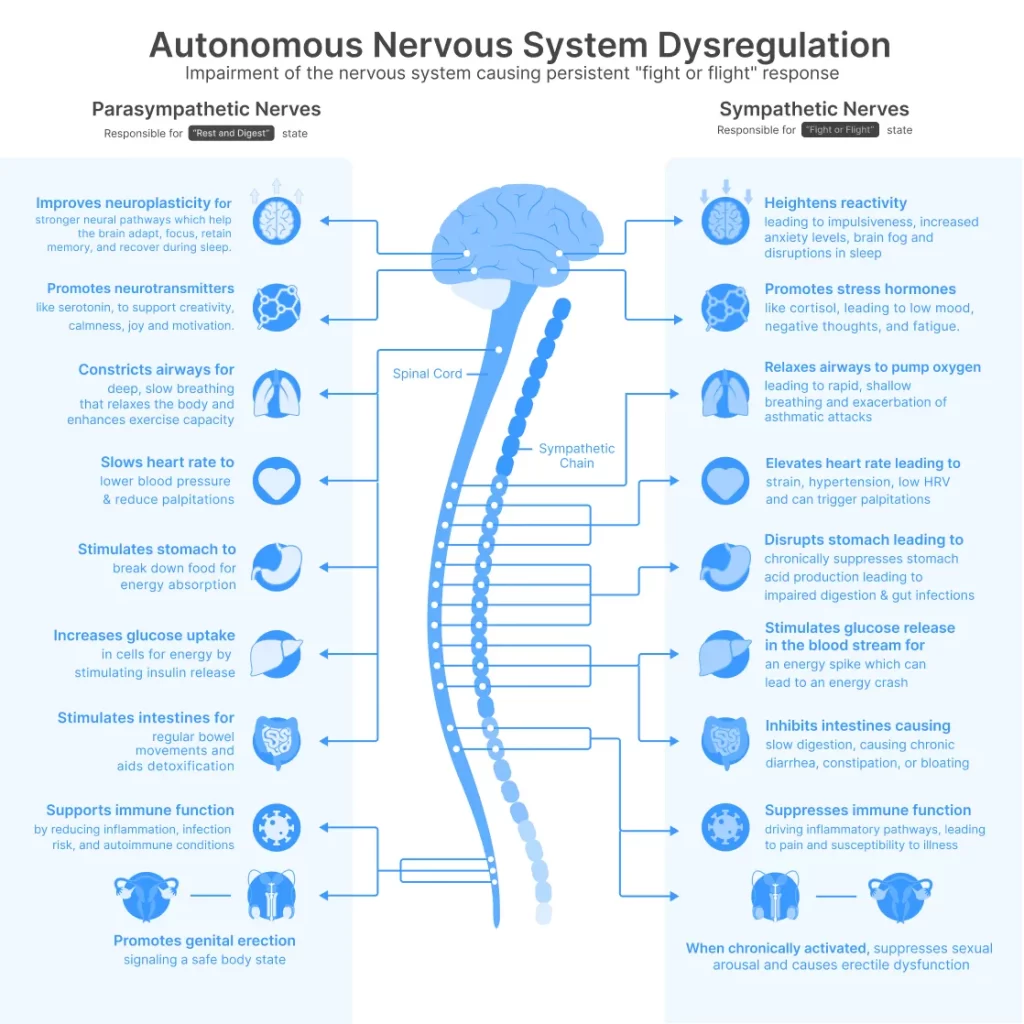

It’s increasingly understood that chronic anxiety is not just “in the mind” – it is deeply linked to the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which controls our involuntary bodily functions. When someone feels anxious, it’s actually their nervous system going into a state of heightened arousal (the fight-or-flight mode). Key physical symptoms of anxiety – a racing heart, fast breathing, tense muscles, stomach butterflies – are caused by a surge of output from the sympathetic branch of the ANS, often described as the fight-or-flight system2. In a healthy scenario, the sympathetic response turns on when a threat is present and then switches off once the threat passes, allowing the body to return to a calm baseline via the parasympathetic branch (the “rest-and-digest” system)2.

In many anxiety disorders, researchers have observed a pattern of nervous system dysregulation: the fight-or-flight response is overactive or misfiring, while the calming parasympathetic signals are underactive2 ‘ 3. In other words, the body’s stress thermostat is set too high. The sympathetic nervous system stays engaged even in relatively non-threatening situations, flooding the body with stress hormones (like adrenaline and cortisol) on a frequent basis. Meanwhile, the mechanisms that should tone down the stress response – primarily the vagus nerve signals that slow the heart and promote relaxation – aren’t effectively counterbalancing the stress state.

This chronic “high-alert” state can exhaust the body and mind. Cleveland Clinic experts note that being stuck in fight-or-flight mode wears the body down and contributes to anxiety and health problems2. Normally, after a scare or challenge, the parasympathetic system (via the vagus nerve) kicks in to bring you back to baseline – lowering heart rate, relaxing muscles, calming the mind2. But if this system is not responding properly, an individual can feel anxious almost continuously, as if the danger never passed. Over time, an overactive stress response can lead not only to anxiety disorders but also to issues like high blood pressure, poor digestion, headaches, insomnia, and a host of stress-related ailments2,4.

Heart Rate Variability: A Window Into Autonomic Balance

One measurable indicator of this nervous system imbalance is heart rate variability (HRV). HRV refers to the variation in time between heartbeats – counterintuitively, a higher variability (i.e. a lot of subtle beat-to-beat variation) is a sign of a healthy, resilient nervous system, whereas low variability (little variation between beats) can signal stress and ANS imbalance5. As Dr. Elijah Behr of Mayo Clinic explains, HRV “measures the balance of nerve activity in the body” – specifically the tug-of-war between the sympathetic (adrenaline-driven) and parasympathetic (vagus-driven) influences on the heart5. When vagus nerve activity is strong, it causes the heart rate to subtly slow down and speed up in a dynamic way; when stress or sympathetic activity dominates, the heart rhythm becomes more monotonic and less variable5, 6.

In people with anxiety disorders, numerous studies show that HRV is often reduced compared to non-anxious individuals. A meta-analysis of 36 studies (over 2,000 anxiety patients vs 2,300 healthy controls) found significantly lower HRV in those with anxiety – reflecting decreased vagal (parasympathetic) tone and an imbalance toward sympathetic activation4. This was true across generalized anxiety, panic disorder, social anxiety and others, indicating a common physiological thread: anxiety is associated with an underactive calming system and an overactive stress response4. Low HRV in anxious individuals is more than an academic finding – it has real implications. It suggests that their bodies struggle to down-regulate stress, potentially increasing risk for cardiovascular issues over time4. Indeed, chronic anxiety has been linked to higher risk of heart disease and sudden cardiac events, likely via this autonomic dysregulation4.

The concept of nervous system dysregulation as a root contributor to anxiety is gaining traction. Rather than viewing anxiety only as excessive worry or cognitive patterns, this perspective sees it as the result of a constantly revved-up physiological state. This opens the door to treatments aimed at directly “rebalancing” the autonomic nervous system – essentially, strengthening the parasympathetic (vagal) activity to rein in the fight-or-flight response. As we’ll explore, one of the most promising targets for doing this is the vagus nerve itself.

The Vagus Nerve: Key to Calming the Body

The vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) is the longest nerve of the autonomic nervous system, running from the brainstem down through the neck to the chest and abdomen7. We have two vagus nerves (left and right), and together they innervate most of our major organs – the heart, lungs, digestive tract, and more7. The vagus is often called the body’s “internal braking system” or “tranquilizer nerve” because it is the main carrier of parasympathetic signals that slow the heart rate, stimulate digestion, and promote relaxation7. When you exhale slowly or when you’re in a safe, rested state, the vagus nerve is actively releasing acetylcholine on the heart to gently slow it, and sending signals to organs that facilitate rest, repair, and digestion2,7.

In essence, the vagus nerve is the counterweight to adrenaline. It helps “disengage” the fight-or-flight response, bringing the body back to homeostasis after stress2. Activating the vagus nerve (or increasing vagal tone) leads to lower blood pressure, a calmer breathing pattern, and a sense of relaxation. This mind-body connection is so strong that stimulating the vagus can actually alter mood and emotional state. That’s why techniques like deep breathing, meditation, or even bearing down as if having a bowel movement (a vagal maneuver) can sometimes abort a panic attack – they work by triggering vagus nerve activity, slowing the heart and calming the brain.

Importantly, the vagus nerve has significant bidirectional communication with the brain. It not only sends commands from the brain to organs, but about 80% of its fibers are sensory – carrying information from the body back to the brain3. This means stimulating vagal fibers in the periphery can influence brain regions involved in mood and anxiety. It also partly explains phenomena like “gut feelings,” since vagus nerve signals from the gut can affect emotional centers in the brain.

Given the vagus nerve’s central role in regulating anxiety and stress responses, it has become a focal point for treatment innovation. The goal is to boost vagal activity (thus restoring autonomic balance) in people whose vagal tone is low. Interestingly, many conventional anxiety treatments likely have an effect on the vagus: for instance, SSRIs are thought to improve heart rate variability (vagal tone) over time as depression/anxiety lift8, and CBT plus relaxation training can increase HRV by teaching the body to activate the vagus during stress. Even exercise and yoga have been shown to improve vagal tone and HRV9, 2. However, a more direct approach is now available: Vagus Nerve Stimulation.

Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS): From Implants to Non-Invasive Therapy

Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) refers to any technique that deliberately stimulates the vagus nerve with electrical impulses to produce therapeutic effects. It was initially developed as an invasive treatment in the 1990s: surgeons would implant a small pulse generator in the chest with electrodes wrapped around the vagus nerve in the neck. This implant device delivers intermittent electrical pulses to the vagus. In 1997, the FDA approved implanted VNS for refractory epilepsy (seizure patients not responding to medications)2. Later, it was also approved for difficult-to-treat depression and investigated for other conditions like cluster headaches and obesity2. Implanted VNS can modulate brain activity via the vagus and has provided seizure reduction and mood improvement in many patients who didn’t benefit from other treatments2.

Notably, early evidence suggested VNS might also help anxiety disorders. Clinical observations and studies found that some epilepsy or depression patients receiving VNS reported reduced anxiety and panic symptoms as a side benefit2. Over the past two decades, research on VNS broadened: scientists started exploring its potential in a wide range of disorders that involve autonomic or inflammatory dysregulation – including anxiety disorders, PTSD, Alzheimer’s disease, chronic inflammation, heart failure, and autoimmune conditions2. The reason VNS could be so broadly useful is that the vagus nerve affects many body systems (brain circuits, immune responses, heart rhythm, etc.). Stimulating it can reduce levels of inflammatory cytokines, reset abnormal heart rate patterns, and alter neurotransmitters in the brain.

However, surgical VNS has drawbacks: it requires an operation to implant, carries surgical risks, and can cause side effects like voice changes or hoarseness (due to the electrode irritating the nerve branch that affects the vocal cords)2. There is also a small risk of cardiac complications (overstimulation causing slow heart rate) in some cases2. Because of these issues, non-invasive approaches have been sought. Fortunately, anatomists found that a small branch of the vagus nerve (the auricular branch) comes to the skin’s surface in the outer ear – specifically, parts of the ear canal and ear concha have vagal nerve fibers11. This means one can stimulate the vagus through the skin at the ear, avoiding any surgical procedure.

Transcutaneous Auricular VNS (taVNS) – Stimulating the Vagus Through the Ear

Transcutaneous VNS (tVNS) refers to stimulating the vagus via electrodes placed on the skin (transcutaneously). One method targets the vagus in the neck, but the most common and accessible method is auricular VNS, which targets the auricular branch of the vagus in the external ear2. This is often abbreviated taVNS. In taVNS, a small electrode is placed on or clipped onto specific points of the ear – typically the tragus or cymba conchae – which are innervated by the vagus. A mild electrical current is passed, which activates the nerve endings and sends signals up into the brainstem, just as an implanted vagus stimulator would10. Essentially, the ear becomes the entry point to influence the vagus nerve and, through it, the entire parasympathetic network.

The big advantage of taVNS is safety and convenience. There is no surgery – it’s as simple as wearing an earbud-like device. Studies have found taVNS to be very well-tolerated, with the most common side effects being minor skin irritation, tingling, or some ear discomfort that usually goes away2. Critically, unlike the implanted method, transcutaneous stimulation avoids directly hitting the cardiac branches of the vagus, so it has not been associated with serious cardiac side effects or vocal cord paralysis2. A recent systematic review of taVNS safety concluded that no severe adverse events were causally linked to the therapy, and overall it is “a safe and feasible option” for patients, with only mild effects (like ear pain or headache in some)2.

For anxiety and related conditions, taVNS offers an exciting new approach: directly treating the dysregulated nervous system. Rather than only using medications to blunt symptoms, taVNS aims to restore balance by boosting vagal activity. Early research is very promising:

- In patients with diagnosed anxiety disorders, preliminary trials have shown symptom reductions with taVNS. For instance, a double-blind randomized controlled trial in 2024 tested taVNS on university students with chronic anxiety. After only two weeks of daily 15-minute sessions, the taVNS group had significantly lower anxiety scores (measured by the Beck Anxiety Inventory) compared to a sham stimulation group, and the improvement persisted at least two weeks post-treatment12. The authors noted the results provide “promising” evidence that taVNS can alleviate anxiety in non-clinical populations, and potentially be a useful neuromodulatory intervention for anxiety conditions12.

- Another randomized trial in 2023 looked at geriatric healthcare workers under high stress (post-pandemic) who had insomnia and anxiety symptoms. Those who received four weeks of taVNS showed marked improvements in sleep quality and a significant reduction in anxiety levels compared to controls (with a highly significant difference, p<0.001)8. This suggests taVNS may help counteract stress-induced anxiety in frontline workers, improving both psychological and physical aspects (like sleep) of well-being.

- In a clinical trial for chronic insomnia (which often overlaps with anxiety), taVNS not only improved sleep quality but also alleviated co-occurring anxiety and depression symptoms in patients. In that sham-controlled trial of 72 patients, those treated with taVNS had significant improvement on insomnia severity and reported decreases in anxiety and daytime fatigue, with good safety and tolerance observed13. Notably, benefits were evident within 4 weeks of use. This demonstrates that taVNS’s effect on the nervous system can translate into multi-faceted improvements – better sleep, better mood, and less hyperarousal – in conditions driven by stress.

- Physiologically, taVNS has been shown to do exactly what we’d hope: increase parasympathetic tone and improve HRV. A 2022 study in healthy volunteers found that a single taVNS session significantly boosted HRV metrics – including higher RMSSD and HF (high-frequency power), which are indicators of vagal activity14. Impressively, some of these changes persisted even after the stimulation ended (during a recovery period), suggesting a carryover calming effect14. The same study noted that participants with initially high sympathetic tone (high LF/HF ratio) experienced the largest reductions in that ratio (a shift toward parasympathetic dominance)14. In plain terms, taVNS made their heart rhythm more variable and flexible – a sign of a healthier, relaxed state. Such findings reinforce that taVNS directly targets the autonomic imbalance in anxiety, increasing vagal nerve output and potentially breaking the cycle of a constantly overactivated stress response.

Clinicians and neuroscientists are now actively studying taVNS in a variety of contexts. For example, an ongoing double-blind trial is evaluating taVNS specifically for generalized anxiety disorder, with brain imaging to see how it modulates fear circuits11. Other researchers are examining its role in post-traumatic stress, major depression (with anxiety), and even physical conditions like post-COVID syndrome where dysautonomia (autonomic nervous system dysfunction) is common10. Early evidence across these studies tends to align: stimulating the vagus nerve helps tilt the body back toward parasympathetic “rest and digest” mode, which can reduce the mental and physical manifestations of anxiety.

Vagal Modulation vs. Traditional Approaches: A Complement, Not a Replacement

A person uses a transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulator. These wearable devices clip onto the outer ear to deliver gentle electrical pulses, engaging vagus nerve fibers to promote calm and autonomic balance.

Given the encouraging results with taVNS, one might wonder how this therapy fits in with (or outperforms) more traditional anxiety management techniques. After all, humans have long sought to calm their nerves through various practices – deep breathing, meditation, yoga, cold plunges, and so on – many of which, we now know, also stimulate the vagus nerve to some degree. The key differences often come down to consistency, control, and evidence.

Breathing Exercises and Meditation: Slow diaphragmatic breathing and mindfulness meditation are staples of anxiety self-help. Indeed, these practices can activate the vagus nerve naturally – for example, exhaling slowly increases vagal signals to the heart, and meditative practice is associated with increased HRV over time2. Many therapists incorporate breathing retraining or mindfulness into anxiety treatment, as it can reduce acute stress in the moment. However, the effectiveness of these methods depends on the individual’s ability to practice them regularly and correctly. Not everyone can easily meditate or breathe away their anxiety during a high panic moment. It takes time, discipline, and training to master these techniques. Compliance is a challenge – busy or very anxious individuals may struggle to adhere to daily meditation sessions or might abandon the practice if they don’t see immediate results. In contrast, taVNS is passive and straightforward for the user: you clip a device to your ear and let it stimulate for 15 minutes, without needing to clear your mind or learn a skill. This makes it a potentially more accessible option for people who find traditional relaxation techniques difficult to stick with.

Biofeedback and Neurofeedback: These are more interactive therapies that use sensors to give real-time feedback on physiological signals (like heart rate, muscle tension, or brainwaves) so that patients can learn to consciously control their stress responses. HRV biofeedback, for instance, trains individuals to breathe in a way that maximizes their heart rate variability, effectively teaching them to increase vagal tone. This has shown positive results for anxiety in some studies – it’s essentially a way of manually exercising your vagus nerve. Neurofeedback targets brain activity; for example, an EEG-based neurofeedback might train a person to increase alpha brainwaves associated with relaxation. While promising, these techniques typically require multiple clinic sessions with expensive equipment, or at-home devices that still need significant user engagement (e.g. wearing an EEG headband like the Muse and focusing on specific mental states). As with meditation, consistent practice is needed to maintain benefits, and the dropout rates can be high. TaVNS, on the other hand, directly engages the vagus nerve electrically without the user having to learn how to do it themselves. You could view it as a shortcut – it achieves through technology what biofeedback tries to teach you to do on your own. The convenience factor is substantial: a device can stimulate your nerve in a controlled way at the press of a button, which some might find preferable to spending 20 minutes in a biofeedback exercise daily.

Lifestyle Gadgets and Apps: In recent years a number of consumer wellness products have targeted stress and anxiety. For example, the Calm app and similar meditation apps provide guided relaxation on your phone. These can be great tools, yet again rely on the user to take time out, follow the guidance, and remain committed. Devices like the Apollo Neuro (a wearable band that emits gentle vibrations) claim to reduce stress by delivering a “soothing touch” sensation that supposedly signals safety to the brain. Apollo’s makers report that their vibration patterns can improve HRV by ~11% and help keep the nervous system in balance6, 15, but independent scientific validation is still limited. Another gadget, the Muse headband, provides neurofeedback for meditation, translating brain signals into guiding sounds to help users reach a calm state. All of these are intriguing and have anecdotal fans, yet they can have inconsistent outcomes – one person might swear by it, while another feels little difference. They also, to varying extents, depend on user compliance (you have to remember to wear the Apollo band and choose the right mode, or use the Calm app regularly, etc.).

Where taVNS devices stand out is in the growing base of rigorous clinical evidence behind them and the directness of their mechanism. They target a specific cranial nerve with known effects on anxiety physiology, and their outcomes can be objectively measured (reducing quantified anxiety scores, increasing HRV, etc., as we’ve seen in clinical trials). This doesn’t mean they work overnight or for everyone, but it places them on firmer scientific ground. Crucially, taVNS can be easily integrated into daily routine – for instance, using a device for 15 minutes each morning – with relatively minimal effort from the user and no requirement of entering a meditative state.

It’s not that one approach must replace the other, either. Many experts view vagus nerve stimulation as complementary to traditional therapies. A person might do CBT to reframe anxious thoughts and use taVNS to settle their autonomic nervous system, the combination potentially yielding better results than either alone. Likewise, one can continue practicing yoga or using a meditation app and incorporate taVNS on particularly stressful days or as an adjunct treatment. Each tool has its place. The key is that for the large subset of anxiety sufferers driven by nervous system hyperarousal, taVNS offers a targeted method to address the biological side of anxiety – the over-firing alarm system – while therapy addresses the psychological side.

The Rise of taVNS Devices like Nurosym

One of the leading products in this space is the Nurosym™ device – a non-invasive, handheld vagus nerve stimulator designed for home use. Nurosym (developed by the neurotechnology company Parasym) exemplifies the new generation of taVNS devices that are making this therapy accessible outside of research labs and clinics. It’s essentially a small wearable ear-clip that delivers controlled electrical pulses to the ear’s vagus nerve fibers. Users can self-administer sessions (typically 15-30 minutes a day) to help manage conditions linked to autonomic dysregulation.

What sets Nurosym apart is its strong grounding in scientific validation and regulatory approval. It is a CE-marked medical device in Europe, meaning it has passed rigorous safety and efficacy evaluations under EU medical device regulations16. In fact, Nurosym is advertised as “the first scientifically proven, CE-marked non-invasive vagal neuromodulation system”16. The technology didn’t emerge overnight – it builds on years of research in bioelectronic medicine. The company has collaborated with major research institutions to test and refine the device. According to Parasym, Nurosym has been utilized or studied by leading medical centers including Harvard Medical School, University College London (UCL), and Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust17. This kind of independent validation is crucial; it indicates that top-tier researchers have been involved in clinical trials and that data has been gathered on the device’s effects in real patient populations.

Indeed, Nurosym has undergone double-blind clinical trials in various conditions17. In a recent 2024 study, patients experienced 35% improvement in anxiety symptoms. In further studies, Nurosym has shown to be a safe and effective tool for relieving symptoms across several domains of health where vagus dysfunction is implicated17 .This includes improvements in “anxious thoughts” and mood, better sleep and energy (important for chronic fatigue and post-viral syndromes), and even benefits in physiological metrics like heart rate variability17. Parasym reports that across all their studies to date, there have been zero serious adverse events with over 3,000,000 stimulation sessions delivered18, reinforcing the excellent safety profile.

From a user perspective, devices like Nurosym are appealing for their simplicity. The Nurosym unit is about the size of a small mp3 player and connects to an ear electrode. With the press of a button, it delivers a pre-programmed stimulation session. There’s no need for the user to adjust complex settings; it’s designed to be plug-and-play. The convenience means people can easily incorporate it – for example, clipping it on while relaxing in the morning or unwinding in the evening. The consistency of daily stimulation is where long-term benefits accrue, akin to a daily medication or daily meditation practice, but here the device is doing the work of modulating your nerves.

Nurosym’s makers highlight outcomes like an average 61% improvement in vagus nerve function in just 5 minutes (as measured by HRV and other biomarkers) in users, indicating a substantial strengthening of parasympathetic tone18. They also note positive feedback from health professionals and integration in multiple ongoing scientific studies16, 17. It has been “trusted by hundreds of health professionals in neurology, cardiology, and bioelectric medicine” according to the company16.

Of course, as with any emerging therapy, maintaining a scientifically neutral stance is important. While the marketing for taVNS devices is optimistic, patients and clinicians should look for peer-reviewed publications of clinical trial results to truly gauge efficacy. Fortunately, more of these are appearing as trials conclude. The field of bioelectronic medicine is burgeoning, and vagus nerve stimulators like Nurosym are at its forefront. They stand on a plausible scientific rationale (fix the faulty relaxation response) and are bolstered by early clinical evidence of benefit without major downsides.

A Balanced Path Forward

For readers searching for solutions to anxiety, the takeaway is this: anxiety disorders have both psychological and physiological components, and addressing both can lead to better outcomes. Conventional treatments (therapy, medication) are effective for many people and remain the first-line approaches1. At the same time, understanding anxiety as a state of nervous system imbalance opens up additional tools. Strengthening your vagus nerve – whether through healthy habits like exercise and deep breathing or through advanced therapies like transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation – can help tackle anxiety at its roots, calming the body’s stress response.

Vagus nerve stimulation, particularly non-invasive auricular VNS, is an exciting development grounded in solid science. It leverages the body’s built-in calming system to combat the very physical underpinnings of anxiety. Reputable institutions like the Mayo Clinic and Cleveland Clinic emphasize building resilience through techniques that enhance vagal tone (meditation, yoga, etc.)2. TaVNS offers a high-tech assist in this same direction – essentially a targeted exercise for your vagus nerve via a convenient device.

As research continues to accumulate, we may find taVNS becoming a mainstream component of anxiety treatment plans, used alongside therapy or as a maintenance tool for those who prefer to minimize medication. Devices like Nurosym have already obtained regulatory approval in Europe and are being evaluated by leading medical centers, which attests to their potential17. For someone suffering from generalized anxiety or panic attacks, this means there could soon be doctor-prescribed neuromodulation devices to use at home, much as one uses a blood pressure cuff or insulin pump to manage other chronic conditions.In conclusion, anxiety is not “all in your head” – it’s in your body’s wiring too. By combining the psychological interventions that help reframe fearful thoughts with physiological interventions that retrain your nervous system (like taVNS), a comprehensive approach to anxiety becomes possible. It’s an approach that aligns with how top health institutions now talk about anxiety: a treatable condition of mind and body, with multiple entry points for therapy. The concept of “hacking the vagus nerve” may have once sounded like science fiction, but today it is a reality supported by medical science. And for the millions of people seeking relief from anxiety, that is very good news.

Sources:

Recent clinical research and expert guidelines have informed this article’s content, including publications from Mayo Clinic and Cleveland Clinic on anxiety disorders and the autonomic nervous system my.clevelandclinic.org my.clevelandclinic.org, meta-analyses on heart rate variability in anxiety pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, and multiple peer-reviewed studies of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation for anxiety and stress reduction frontiersin.org hoolest.com researchgate.net. Additionally, data and claims regarding the Nurosym device are drawn from the manufacturer’s documentation and affiliated institutional research nurosym.com nurosym.com, presented here with a neutral perspective for educational purposes. Overall, the integration of these sources paints a hopeful picture of emerging, science-backed solutions for anxiety that address both symptoms and their root causes in the nervous system.

- Cleveland Clinic. (n.d.). Anxiety disorders: Causes, symptoms, treatment & types. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/9536-anxiety-disorders

- Lin, Y. (2023, April 20). Your vagus nerve may be key to fighting anxiety and stress. Cleveland Clinic. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/what-does-the-vagus-nerve-do

- Kim, A.Y., Marduy, A., de Melo, P.S. et al. Safety of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 12, 22055 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-25864-1

- Chalmers, J. A., Quintana, D. S., Abbott, M. J., & Kemp, A. H. (2014). Anxiety Disorders are Associated with Reduced Heart Rate Variability: A Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in psychiatry, 5, 80. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00080

- Theimer, S. (2024, July 30). Your wearable says your heart rate variability has changed. Now what? Mayo Clinic News Network. https://newsnetwork.mayoclinic.org/discussion/your-wearable-says-your-heart-rate-variability-has-changed-now-what/

- Shmerling, R. H. (2021, September 22). Harvard Health Ad Watch: Can a wearable device reduce stress? Harvard Health Publishing. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/harvard-health-ad-watch-can-a-wearable-device-reduce-stress-202109222601

- Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Vagus nerve. Wikipedia. Retrieved May 9, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vagus_nerve

- Hoolest Inc. (n.d.). Clinical evidence for vagus nerve stimulation for stress. Retrieved May 9, 2025, from https://hoolest.com/blogs/news/clinical-evidence-for-vagus-nerve-stimulation

- Cleveland Clinic. (2022, March 10). 5 ways to stimulate your vagus nerve. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/vagus-nerve-stimulation

- Geddes, L. (2023, August 23). The key to depression, obesity, alcoholism – and more? Why the vagus nerve is so exciting to scientists. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/aug/23/the-key-to-depression-obesity-alcoholism-and-more-why-the-vagus-nerve-is-so-exciting-to-scientists

- Lai, J., Liu, J., Zhang, L., Cao, J., Hong, Y., Zhang, L., Fang, J., & Wang, X. (2025). Effect of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation with electrical stimulation on generalized anxiety disorder: Study protocol for an assessor-participant blinded, randomized sham-controlled trial. Heliyon, 11(4), e42469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2025.e42469

- Ferreira, L. M. A., Brites, R., Fraião, G., Pereira, G., Fernandes, H., de Brito, J. A. A., Pereira Generoso, L., Capello, M. G. M., Pereira, G. S., Scoz, R. D., Silva, J. R. T., & Silva, M. L. (2024). Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation modulates masseter muscle activity, pain perception, and anxiety levels in university students: A double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 18, Article 1422312. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2024.1422312

- Zhang, S., Zhao, Y., Qin, Z., Han, Y., He, J., Zhao, B., Wang, L., Duan, Y., Huo, J., Wang, T., Wang, Y., & Rong, P. (2024). Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Chronic Insomnia Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA network open, 7(12), e2451217. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.51217

- Geng, Duyan & Liu, Xuanyu & Wang, Yan & Wang, Jiaxing. (2022). The effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on HRV in healthy young people. PLOS ONE. 17. e0263833. 10.1371/journal.pone.0263833.

- Apollo Neuroscience, Inc. (2023, February 3). Peer-reviewed clinical study: Apollo Neuro is the first wearable technology scientifically proven to improve HRV. https://apolloneuro.com/blogs/news/peer-reviewed-clinical-study-proven-to-improve-hrv

- Nurosym. 11 reasons why people integrate Nurosym in their daily health routine. https://nurosym.com/pages/11-reasons-why-people-integrate-nurosym-in-their-daily-health-routine

- Nurosym. Advanced vagus nerve stimulation. https://nurosym.com/en-at/pages/advanced-vagus-nerve-stimulation

- Nurosym. HRV. https://nurosym.com/pages/hrv